Your Guide to Treatment of Timber in NZ

Timber treatment is a bit like giving wood a permanent, heavy-duty raincoat and a suit of armour all in one. By infusing the timber with preservatives, we protect it from everything that wants to break it down—rot, insects, and general decay—drastically extending its working life.

This process is absolutely vital here in New Zealand. Our climate, with its high humidity and moisture levels, can be incredibly tough on timber, making untreated wood a prime target for rapid deterioration and, eventually, structural failure.

Why Timber Treatment Is So Critical in New Zealand

Think about our weather for a moment. From the damp, subtropical north to the frosty, wet winters down south, moisture is the number one enemy of timber. It creates the perfect breeding ground for fungi and rot, which can compromise a structure surprisingly quickly.

And it’s not just the weather. Our environment is also home to some notoriously destructive pests, like the common house borer (Anobium punctatum), which can quietly turn solid structural beams into nothing more than sawdust. That's why timber treatment isn't just a "nice-to-have"; it's a non-negotiable step for ensuring the safety, integrity, and longevity of any building project in Aotearoa.

The Big Shift from Native Timbers to Treated Pine

It wasn't always this way. For generations, New Zealand builders relied on the incredible natural durability of our native timbers like tōtara and kauri. These dense, beautiful hardwoods were packed with their own natural oils and resins, making them highly resistant to both decay and insects.

But the early days of the timber industry completely reshaped our landscape. Huge swathes of native forest were cleared to make way for pasture. As awareness and concern over this depletion grew, the focus shifted towards sustainable forestry, leading to the widespread planting of exotic species.

Today, radiata pine makes up over 91% of New Zealand's planted production forests. It's a fantastic timber—fast-growing, versatile, and sustainable. But it has one major drawback: it lacks the natural defences of our native giants.

This is where modern preservation methods come in. Without effective treatment, radiata pine simply wouldn't be up to the task for most construction uses. It highlights just how vital the treatment process is to our modern building industry. If you're interested in the broader context of our primary industries, you can explore various topics related to New Zealand's agriculture and farming sectors.

Making Sense of Hazard Classes

To keep things straightforward, New Zealand uses a system of Hazard Classes, often just called H-levels. This framework is designed to match the level of preservative treatment to the specific environment the timber will face, ensuring it has the right amount of protection for the job.

The core idea is simple: the higher the risk from moisture and pests, the higher the Hazard Class you need. This system is brilliant because it prevents both under-treatment (which leads to failure) and over-treatment (which is wasteful and costly).

Here’s a quick rundown of what these levels mean for everyday projects:

- Low Hazard (e.g., H1.2): This is for interior framing and other timber that will be kept dry for its entire life.

- Medium Hazard (e.g., H3.2): The go-to for exterior structures like decks, cladding, and fences that are exposed to the weather but aren't touching the ground.

- High Hazard (e.g., H5): Essential for any timber that will be in direct contact with the ground, like fence posts, poles, and retaining walls.

Understanding Different Timber Treatment Methods

Just like there are different ways to cook a meal—baking, frying, or slow-cooking—there are several distinct methods for treating timber. Each technique is designed to give the wood a specific level of protection, infusing it with preservatives that act as a shield against the things that want to break it down. Getting your head around these methods helps demystify what happens to timber long before it arrives at your local merchant.

The most common and heavy-duty method we use in New Zealand is pressure treatment. Think of a dry kitchen sponge. If you just dip it in water, only the outside gets wet. But if you squeeze it underwater and let it expand, it soaks up water right into its core.

Pressure treatment works on a similar principle. Timber is loaded into a huge, sealed cylinder, and a vacuum sucks all the air from the wood's cells. Then, the preservative solution—like the tried-and-true CCA (Copper Chrome Arsenate) or the more modern ACQ (Alkaline Copper Quaternary)—is flooded in under immense pressure. This forces the protective chemicals deep into the wood’s cellular structure, ensuring tough, long-lasting protection from the inside out.

Penetration vs Protection on the Surface

Not all timber needs the full-on defence of pressure treatment. For different jobs, other methods offer the right balance of protection and efficiency. One of these is diffusion, a much gentler process.

In diffusion, freshly cut, green timber (which still has high moisture content) is dipped in or sprayed with a preservative solution, usually containing boron compounds. The wood's own moisture helps the preservative slowly and naturally spread—or diffuse—throughout the timber over several weeks. This method is perfect for timber that will be used in low-risk indoor situations, like the framing inside your walls (H1.2), where it only needs to fend off insects like borer, not the weather.

Another approach is applying surface coatings. Think of this like putting a protective layer of sunscreen on your skin. While it doesn't sink in deeply, it forms a barrier on the outside. Stains, oils, and specialised paints can shield timber from moisture and UV rays, but they’re no substitute for proper preservative treatment in structural timber. They are best used as an extra layer of defence and for ongoing maintenance.

Modern and Natural Alternatives

As awareness around sustainability and health grows, so does the interest in different ways to treat timber. These modern techniques offer effective protection, often with a lighter environmental footprint.

One of the most interesting is thermal modification. This process is like carefully ‘baking’ the wood in a special oxygen-free kiln at high temperatures. This controlled heating changes the wood's cellular structure, making it far more stable and resistant to moisture and rot without using any chemicals at all. Thermally modified timber is a fantastic option for cladding and decking where you want a natural, chemical-free finish.

"Exploring different treatment methods reveals a core principle in construction: the solution must match the problem. A fence post needs a different kind of armour than an indoor beam. Understanding the 'how' behind the treatment empowers you to make smarter, safer, and more durable choices for any project."

Another popular, less-toxic option is boron treatment. Boron is a naturally occurring element that is highly effective against insects but has low toxicity to us, making it a safe choice for indoor environments. It’s the key ingredient in the H1.2 treated timber used for house framing right across New Zealand. However, because boron is water-soluble, it will wash out if it gets wet, which is why it's strictly for dry, indoor use.

For those keen to develop their hands-on abilities further, exploring a range of practical skills for DIY projects can provide the confidence needed to tackle any job, big or small.

To help you see how these different methods stack up for common jobs around the home, here’s a quick comparison.

A Quick Comparison of Timber Treatment Methods

This table summarises the common treatment methods you'll encounter in New Zealand, highlighting what they're best for and what makes them unique.

Choosing the right treated timber comes down to understanding the environment it will live in and the job it needs to do. With this knowledge, you're well-equipped to pick the perfect material for a project that will stand the test of time.

How to Choose the Right Treated Timber

Picking the right treated timber can feel like a massive decision, and honestly, it is. Getting it wrong can lead to premature rot, insect invasions, and even structural failure down the track. It’s a bit like choosing tyres for a vehicle; you wouldn't put slick city tyres on a farm ute destined for muddy Canterbury paddocks.

In the same way, the secret to a long-lasting timber project here in New Zealand is matching the timber’s protective treatment to the exact environment it will live in. This is where New Zealand's Hazard Class system, or H-levels, becomes your best friend. It’s a simple, logical framework designed to take all the guesswork out of the decision.

Decoding the New Zealand Hazard Class System

The Hazard Class system is essentially a scale that tells you the level of preservative treatment needed to protect timber from decay and insects in different scenarios. The logic is dead simple: the greater the risk, the higher the H-level your timber needs.

Understanding this system isn't just about following best practices; it's a core requirement for complying with the NZ Building Code. It ensures your work is safe, durable, and truly built to last. Let's break down the common H-levels you'll bump into on any job site.

H1.2 For Protected Indoor Framing: This is your standard for timber used inside a building's envelope, like wall framing and roof trusses. It’s kept dry and shielded from the weather, so the treatment is mainly about guarding against insect attacks, like the common house borer.

H3.2 For Outdoor Above-Ground Use: This is the workhorse for most exterior projects. H3.2 treated timber gets a higher dose of protection, making it the right choice for decking, fencing, pergolas, and cladding—basically, anything that's exposed to the rain and sun but isn't touching the ground.

H4 For Ground Contact (Non-Structural): When your timber is going straight into the dirt but isn't holding up a heavy load, H4 is what you need. Think fence posts and landscaping timber, where there's a constant risk of moisture and decay from the soil.

H5 For Ground Contact (Structural): This is the next level up, designed for critical structural jobs. H5 is a must for house piles, retaining walls, and crib walls—components that are not only in the ground but are also bearing significant loads.

H6 For Marine Environments: Reserved for the absolute toughest conditions, H6 is for timber in marine applications like jetty piles and wharf decking. It’s treated to handle constant immersion in saltwater and fend off attacks from marine organisms.

Matching the H-Level to Your Project

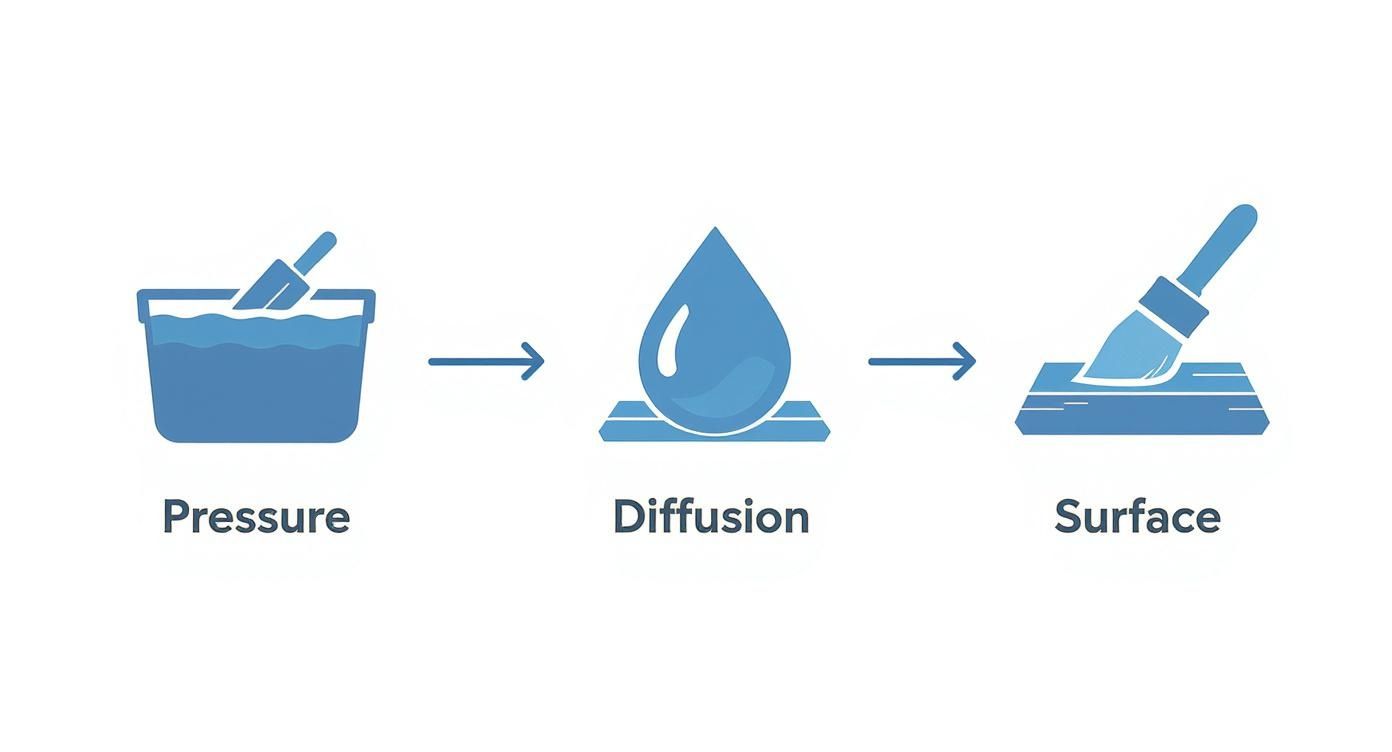

To make things even clearer, this infographic gives you a great visual guide to how these protection levels are achieved through different treatment processes.

As the diagram shows, the methods—from high-pressure infusion to simple surface coatings—are chosen based on where the timber will end up and how long it needs to last.

Here’s a crucial point: you can't just 'paint on' a higher hazard rating. The protection level is locked in during the initial treatment process. That's why picking the correct H-level right from the start is non-negotiable for any timber treatment project.

The economic importance of getting this right is massive. In 2024, New Zealand's forestry and wood processing sectors employed around 42,000 people and kicked $3.6 billion into our GDP. Our heavy reliance on plantation radiata pine means these treatment standards are the backbone of the industry, ensuring our timber performs reliably and supports our economy. You can explore more data on the plantation forestry statistics that shape our industry.

Always Check the Identification Tag

So, how do you know you’re buying the right stuff? Every piece of compliant treated timber sold in New Zealand has to be clearly marked. Look for a plastic tag stapled to the end of the board, or a stamp printed along its length.

This little identification mark is your guarantee of quality and compliance. It will tell you three key things:

- The Treatment Plant: The unique number or name of the facility.

- The Preservative Used: A code for the chemical, like CCA or ACQ.

- The Hazard Class: The all-important H-level, for example, H3.2.

Never use unmarked timber for a project where the building code specifies a hazard class. That small tag is your assurance that the wood is fit for purpose and won't let you or your client down. Just remember, this information is a guide and should never replace formal building advice or the expertise of a professional.

Safety Precautions and Environmental Impact

While treated timber is built tough to last, the chemicals that give it this strength demand a healthy dose of respect. It’s a bit like a powerful tool in your workshop; incredibly useful, but you need to know how to handle it correctly to keep everyone safe. Getting the basics of safety right isn't just a suggestion—it's essential for anyone working with this material.

The golden rule is to shield yourself from direct contact and from breathing in the dust. Sawdust from treated timber is a different beast to regular wood dust. It’s carrying the preservative chemicals, and you definitely don’t want that in your lungs or irritating your skin.

Before you even think about making that first cut, gearing up is the first and most important job.

Essential Personal Protective Equipment

Your Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) is your first and best line of defence. Whenever you’re cutting, sanding, or just handling treated timber, make sure you're wearing the following:

- Gloves: A sturdy, well-fitting pair of gloves is a must to keep chemical residues off your skin.

- Dust Mask: Don’t skimp here. A quality, properly fitted dust mask (P2 or equivalent) is crucial for stopping fine sawdust particles at the source.

- Eye Protection: Safety glasses or goggles are non-negotiable for protecting your eyes from dust and flying debris.

- Long Sleeves: Covering your arms is a simple way to reduce skin exposure, especially during a long day on the tools.

A critical safety warning for every Kiwi home: Never burn treated timber offcuts or old treated wood. The preservatives, especially in older CCA-treated timber, can release toxic chemicals like arsenic into the air when burned. This poses a serious health risk and contaminates your fireplace, BBQ, and surrounding environment.

Proper disposal is the only safe way to go. Small offcuts can usually be popped into your general household waste. For bigger quantities from a reno or demo job, they’ll need to go to an approved landfill. It's always a good idea to check your local council's specific guidelines.

Environmental Considerations and Sustainability

The conversation around treated timber is increasingly focused on its environmental footprint, and for good reason. For decades, the industry has been pushing towards smarter preservatives that are not only more effective but also gentler on the environment. This shift is happening thanks to both tighter regulations and Kiwis asking for greener building options.

A huge step forward in New Zealand has been the move to preservatives like ACQ (Alkaline Copper Quaternary), especially for residential projects. ACQ is a fantastic alternative to the old CCA treatments because it doesn’t contain arsenic or chromium. This makes it a much better choice for things your family might come into contact with, like veggie garden beds, kids' playgrounds, and backyard decks.

It's well worth looking into the full range of modern solutions, including non-toxic wood preservatives, to see just how far the technology has come.

Beyond the treatment process itself, the real story of sustainability starts in the forest. Here in New Zealand, the vast majority of our structural timber comes from sustainably managed radiata pine plantations. These aren't ancient native forests; they're purpose-grown crops managed in a renewable cycle of planting, growing, and harvesting.

When you choose timber certified by groups like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), you're backing responsible forestry. This ensures the wood is sourced in a way that protects biodiversity, respects communities, and keeps our forests healthy for generations to come.

How to Maintain and Extend the Life of Your Timber

Getting your timber treated from the get-go is the critical first line of defence against rot and insects. But it’s a mistake to think that’s the end of the story. Think of initial treatment as the foundation; long-term maintenance is the framing and cladding that protects your investment against New Zealand's harsh sun and driving rain for decades.

Even the most thoroughly treated timber isn't bulletproof. While the preservation process works its magic deep inside the wood, the surface is still left to face the elements day in, and day out. Constant exposure to UV rays and moisture will eventually cause the timber to fade, crack, and take on that classic weathered look. A proactive maintenance schedule is your best bet for adding that crucial extra layer of protection.

Creating a Protective Surface Barrier

Applying a quality surface coating is hands-down the most effective maintenance job you can do. A good stain, oil, or paint acts like a shield, stopping surface water from soaking in while protecting the wood fibres from the sun's damaging rays. This is especially important for horizontal surfaces like decks, which really take a beating from the weather.

The way we harvest timber in New Zealand has changed dramatically. Between 2011 and 2023, the national harvest was a massive 32.5 million cubic metres of wood per year, with more than half of that shipped offshore as raw logs. Radiata pine, which isn't a naturally durable timber, now makes up the bulk of our plantation forests. This makes that initial treatment and ongoing maintenance absolutely vital for the lifespan of our country's building stock. You can find more insights on NZ's forestry sector on Gresham House.

Even after that first treatment, picking the best paint for treated wood projects is key to keeping it looking good and holding strong. A high-quality coating will seriously extend the life of any timber structure.

Your Practical Timber Maintenance Schedule

A simple, regular check-up and recoat schedule will keep your timber looking sharp and doing its job. How often you need to do this really depends on how exposed the structure is to the elements.

Think of timber maintenance like servicing your car. You don't wait for it to break down before you change the oil. Regular, preventative care is far more effective and less costly than dealing with a major failure down the line.

Here’s a straightforward schedule to get you started:

- Annual Inspection: At least once a year, give your timber structures a proper clean and a good look-over. Keep an eye out for any signs of wear, mould, or damage.

- Decks (High Exposure): Decks are high-traffic, fully exposed surfaces. You should plan to re-stain or re-oil yours every 2-3 years to maintain its protective barrier and colour.

- Fences & Pergolas (Medium Exposure): These vertical surfaces are better at shedding water. They’ll usually need a recoat every 4-6 years, depending on their condition.

Troubleshooting Common Timber Issues

After a few years, you might start to notice a few common problems cropping up. The good news is that if you catch them early, they’re pretty easy to manage.

1. Surface Mould and Mildew

This usually shows up as black or green spots in damp, shady areas.

- Solution: Give the area a scrub with a specialised timber cleaner or a simple mix of water and household bleach. Rinse it off thoroughly, let it dry completely, and then think about applying a fresh coat of sealant. It's also worth noting that looking after garden structures goes hand-in-hand with good garden care, a topic we cover in our practical courses in horticulture.

2. Cracking and Splitting (Checking)

Small cracks are just a natural part of timber weathering as it expands and contracts with moisture changes.

- Solution: You can't stop checking completely, but you can manage it. Keeping the timber well-sealed with a quality oil or stain will slow down moisture changes and reduce how severe the cracks get.

3. Warping and Cupping

This happens when one side of a board dries out faster than the other, causing it to bend and curl.

- Solution: Prevention is the best cure here. If you can, make sure all sides of a board are sealed before you install it. For boards that are already warped, a good clean and seal can help stabilise them, but you might need to replace any really bad ones.

Common Questions About Timber Treatment

Once you've got your head around the basics, a few practical questions always pop up on the job. Let's tackle some of the most common queries that Kiwi DIYers and homeowners have when it comes to treated timber. The goal here is to give you quick, clear answers that build your confidence and lock in what you've already learned.

Each of these questions dives into a real-world scenario you’re likely to face, clearing up any confusion and adding a bit more context.

Can I Use Outdoor Treated Timber Inside My House?

The short answer is no, it's a really bad idea. Timber treated for high-hazard outdoor use (like H4 or H5) is loaded with much higher concentrations of chemicals designed to fight off constant moisture and ground contact. That’s serious overkill for the inside of your home.

For interior framing, the New Zealand standard is H1.2 for a reason. This boron-based treatment gives you all the protection you need against insects in a dry, covered space, without bringing the heavy-duty outdoor chemicals indoors. Always match the timber to the job for safety and performance.

What Is the Difference Between H3.1 and H3.2 Timber?

This is a great question. While both H3.1 and H3.2 are for outdoor, above-ground projects, the real difference is how much weather they can handle. Think of H3.1 as the right choice for spots that are somewhat sheltered from the rain, like painted fascia boards or veranda posts tucked under a roofline.

On the other hand, H3.2 is the go-to standard for anything that’s regularly exposed to the full force of New Zealand’s weather. It's the tougher, more reliable option for decks, fences, pergolas, and balustrades. For most classic Kiwi backyard projects, H3.2 is simply the smarter, more durable choice.

Just remember, you can’t add more protection later. Spending a little extra on H3.2 from the start is a wise investment in your project's lifespan, especially if you live in a rainy part of the country.

How Can I Tell What Treatment My Timber Has?

This is a critical one, but thankfully, it’s pretty straightforward. In New Zealand, all treated timber that complies with the standards must be clearly and permanently marked. This mark is your guarantee.

You'll either find a stamp printed along the wood or, more commonly, a small plastic tag stapled to the end of the board. This tag tells you everything you need to know:

- The unique code for the treatment plant.

- The preservative used (e.g., ACQ or CCA).

- Most importantly, the Hazard Class (e.g., H3.2 or H5).

If you come across timber with no markings, don't use it for anything that requires a specific treatment level under the NZ Building Code. That little tag is your proof of quality, safety, and durability.

Is Timber from Vegetable Gardens Made from Treated Timber Safe?

This is a very common and totally understandable concern for anyone growing their own kai. The good news is that modern treated timber is generally considered safe for building vege gardens. Most timber sold for residential projects these days, like H4 sleepers, is treated with ACQ (Alkaline Copper Quaternary).

ACQ replaced the older CCA treatments, which contained arsenic, for most uses where the public might come into contact with it. Plenty of research has shown that any leaching from ACQ-treated timber into the soil is minimal, and plants are extremely unlikely to absorb these compounds in amounts that would pose any health risk.

If you want extra peace of mind, you can always line the inside of your timber garden beds with a heavy-duty, food-grade plastic liner. This creates a solid barrier between the wood and your soil. The most important thing is to never use old, unidentified treated timber for growing food, as it could be the older CCA type.

At Prac Skills, we're all about empowering Kiwis with the know-how to tackle projects safely and with confidence. Our online courses are built to give you practical, NZ-focused skills you can use straight away, whether you're growing a business or just a backyard vegetable patch. Explore our range of courses at Prac Skills and start building your expertise today.

.webp)